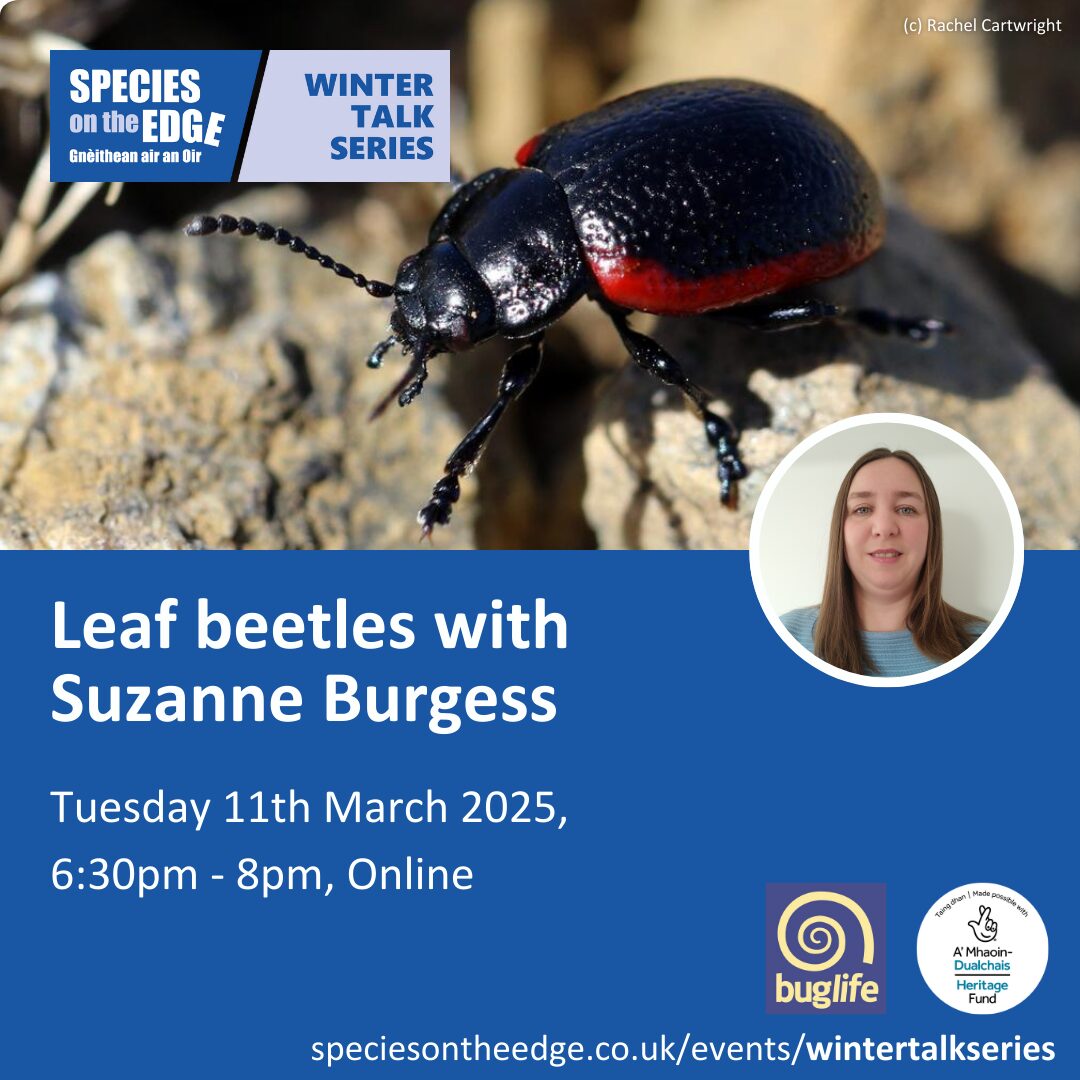

On 11th March 2025 we had the third talk in our 2024/25 Winter Talk Series: Leaf beetles with Suzanne Burgess. Suzanne Burgess is Development Manager with invertebrate conservation charity Buglife, one of the Species on the Edge partners. It was a fascinating talk, taking a deep dive into the shiny, colourful world of leaf beetles, with lots of practical guidance on identifying leaf beetles, including one of our Species on the Edge target species, the plantain leaf beetle.

Watch the full talk on YouTube below. You can also find the transcript for the talk and a list of resources on this page too. If you are interested in getting involved in our work for the plantain leaf beetle in Orkney, Shetland or the North Coast, get in touch with your local team to find out how you can help.

North Coast: Sarah Bird – sarah.bird@plantlife.org.uk

Orkney: Sam Stringer – samantha.stringer@rspb.org.uk

Shetland: Gareth Powell – gareth.powell@rspb.org.uk

Transcript

00:00:05 Liz Peel

Welcome everybody. My name is Liz Peel. I work for Butterfly Conservation. I’m one of the Species on the Edge Project Officers, and I’m based over in Argyll and the Inner Hebrides. I actually live on the Isle of Mull, which is rather nice. This is the third of our series of winter talks. And this one is kindly being presented by Suzanne Burgess from Buglife and it’s about leaf beetles as you all know. Now, Species on the Edge is a Scotland-wide programme. It focuses on the coastal and island communities and the aim of the project is to work with communities to help preserve and conserve and protect our 37 rare species across a whole range of taxa. It involves eight conservation organisations and it’s very kindly funded by The National Lottery, which is great. Tonight, we are going to talk for about 45/50 [minutes], maybe an hour, and then have some questions. There are a lot of people on the call. So, what we’ve been doing is asking people to pop their question in the chat and then my co-host Sally from Buglife will read out the questions once the presentation is finished and we’ll try and make sure we don’t miss anybody in that way. Once we’ve run out of time, if you have any more questions, then please feel free to e-mail us afterwards. We’ll also pop a link to the evaluation form in the chat at the end so you can download the link straight away and fill the evaluation forming for us, if you would be so kind. That helps us assess what we’ve done and will hopefully help us plan next winter’s winter talk series.

So without any further ado, I will hand over to Suzanne from Buglife for her lovely talk. Thank you, Suzanne.

00:02:08 Suzanne Burgess

Thank you for inviting me along today. I will now share my presentation. There we go. And apologies if I start having a coughing fit. I’m recovering from a cold, but I am much better today.

So I am Development Manager with Buglife and actually help support the development of projects across the country. But I have a great fondness for leaf beetles. When I started with Buglife 15 years ago looking at the brownfield sites in Falkirk, I fell in love. Well, I already loved beetles, but I fell in love with leaf beetles, mostly because of the shininess, but also because of their association with plants and the colours and the variety. So hopefully today, tonight, we’ll all learn a little bit more about leaf beetles and learn to love them as much as I do.

Firstly, who are Buglife? If you don’t know who we are, we’re the only organisation in Europe concerned with the conservation of all invertebrates. Our aim is to halt invertebrate extinctions and achieve sustainable populations of invertebrates in the UK. So we do this by trying to inspire people to look at the small things that run the planet a little bit differently, so they appreciate them. We do this by raising awareness through events, talks or conservation projects. We have a whole range of different practical conservation projects across the country, from our peatlands to wildflower grasslands restoration, and also the work that Sally’s been doing and Liz on Species on the Edge, which I’ll talk a little bit more about later. We also do get involved with shaping policy within government too.

So, why invertebrates? They are vital, providing us with a number of free ecosystem services that are worth millions of pounds globally. So, they help manage our soils, recycle nutrients, manage our waste, they help control pest species, they are food for us and other animals and, of course, pollination. So, all of these tasks are vitally important for us to survive, and invertebrates are vital for that link as well.

Now in the UK, there are over 40,000 species of invertebrates. So, before everybody joined us, we were talking about this and how vast and diverse they all are. So, I’m not an expert in any one group – I love beetles – but there’s a whole range of other invertebrates that I’m interested in just because of the diversity.

So, a bit of background about beetles before we go on to leaf beetles. So, beetles are, of course, insects. All insects have a head, a thorax and abdomen, and three pairs of jointed legs. Now, beetles are amazing. They are all in the order Coleoptera, which means sheath wing. There are over 400,000 species that have been described so far, so of course there’s a lot more than that that have not been described due to the size of them and the habitats that have not even yet been studied that support them. And they inhabit nearly every biological niche, from the tundra to the rainforests. Globally, there is no other group of animals that exhibit such range in size, colour or shape.

And they’ve been around for millions of years. So, they’ve evolved this specific design, the shape that works, and they’ve not really needed to change much. So, the oldest, undisputable beetle fossil dates from the Early Permian almost 300 million years ago. They belong to the extinct taxon the Protocoleoptera. But several of the modern suborders, including our leaf beetles and ladybirds and ground beetles, they evolved during the Jurassic period.

So, there’s a couple of examples there of leaf beetles in the fossil record, so just shows how amazing beetles are, that they’ve been around for such a long, long time. Now, I’ve already said they come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Now interesting that the smallest beetles in the world all belong to the feather winged family. So the Bolivian feather-wing is only 0.3 millimetres long, so it’s incredibly, incredibly tiny. The feather winged beetles are amazing. Their wings aren’t typical as of other beetles, their wings are kind of feather-shaped and that actually helps with the lift as they try to fly because they’re so small as well.

And then compare that 0.3 millimetres to our largest beetle in the world. There’s a few that are quite large, but this is one, the Brazilian longhorn that can reach up to 17 centimetres in length. And it’s so strong it can break a pencil in its jaws. But generally, they’re not as big as that. There’s a huge range of sizes.

In the UK, our largest species of beetle is not a leaf beetle, unfortunately, but it is this beautiful creature, this stag beetle, and they can grow up to 9 centimetres in length.

Well, what makes a beetle a beetle? So, they’ve got three regions. You’ve got your head, thorax and abdomen, which is what all insects have. They have a hard exoskeleton, including the four wings. So they’ve they’ve got one pair of wings that are used for flying. The other pair, the elytra are what cover the wings that are used for flying and the abdomen for protection. And they’re hard. So the elytra protect the main body of the beetle. They’ve got antennae which are usually between six and 11 segments long. And they’ve got biting mouth parts, which is incredibly important because of another group of insects, the Hemiptera, True bugs, that can sometimes be mistaken for beetles. But for beetles, the elytra always meet in the middle, where it is with Hemiptera, the true bugs, so they are things like shield bugs or plant bugs from the family Miridae, and even the leaf hoppers and the aphids, they’re all within the Hemiptera. They’ve never got biting mouth parts. They’ve got a tube, a sucking mouth part, which they use to suck up plant goodness or they stab their insects and then they feed by sucking all the insect goodness. So beetles never have a sucking mouthpart, so it’s always biting, and their elytra always meet in the middle, whereas Hemiptera, they’re usually a Y shape or even an X shape, depending on the group.

Another thing that makes the beetle a beetle is they undergo complete metamorphosis, which I will talk about.

And now this is just a general example of a beetle which shows what a beetle looks like. When we think of beetle I think this is what most people think of, a little brown beetle, but there are so many other colours and shapes.

Now I’ll talk about complete metamorphosis in a little bit, but firstly just a little bit more about the body.

So beetle antennae come in all sorts of shapes and sizes as well, just like the beetles themselves for various reasons. So they can be thread-like as in example A or they can be comb like in B or they can be serrated. Some, the lamellate, the plate-like antennae, they are on the species such as the chafers and the dung beetles and the carrion beetles, and they’re filled with chemoreceptors that help them smell out and detect things like dung or dead animals, depending on what they feed on. And G, the elbowed and clubbed, that’s typical of the weevils.

Leaf beetles typically have 11 antennae segments, but there is one group that’s got 10. Their antennae are generally a bit like C or D or just kind of a bit in between to be honest; there’s nothing really special about the leaf beetle antennae.

The legs, now all the different families of beetles have evolved different shaped legs, so ground beetles, their legs are long and very thin, and they’re for running fast, for chasing and hunting their prey. Water beetles have got fine swimming hairs on the tarsi to help them swim through the water.

Now dung beetles have got expanded femur that are modified for digging and fighting, and leaf beetles have got heart-shaped tarsi, and that’s probably to help them when they’re walking over plants, especially on the underside for grip.

Now a little bit about the beetle life cycle and I’ve used a leaf beetle as an example here. So, I mentioned the word holometabolism. Basically, what that means is they undergo complete metamorphosis where the larvae look completely different to the adult and they change completely when they’re in their pupal form. Whereas other insects such as grasshoppers and the Hemiptera, they undergo incomplete metamorphism, so the larvae, the nymphal stage, looks very similar to the adults and they don’t completely change during the pupal stage. They just grow through their instars. So, with beetles, just like butterflies and flies, they start out as a little egg and after a few days the eggs will hatch and then the larvae will appear. The larvae will go through a few, two/three different instar stages before they form their pupa. And I think actually I’m not sure if that’s a leaf beetle pupa or I might have had to use a ladybird as I was struggling to find pictures of leaf beetle pupa for this talk, but they’re again very similar, but they go through their pupal stage before becoming adults. And then the adults, of course, lay eggs and the whole life cycle starts again.

So within their life cycle, the general life history will depend on the species and the families, and of course within families there will be differences as well. So some species will have one generation per year, others will have one generation that takes a bit longer than a year, maybe even up to two years, it just depends. So that might be things like the aquatic beetles that take a couple of years to grow within a pond as a larval and then they’ll emerge and become an adult in the water as well. So it just, it really just depends.

Some beetles go through periods of dormancy where the adults are actually present all year but in some stages where it’s really, really cold, they will just kind of estivate and go and rest for a little while before emerging when the weather gets a bit better. And sometimes you get overlapping generations, so you can find the larval stages around with the adults – it all varies. Even within the leaf beetles, they all do this as well.

Now the larvae of beetles, they generally have a darkened head capsule, and remember those chewing biting mouth parts. Even the larvae have that, and they can bite some of the big ones, even some of the big beetles, the diving beetles, they do have a very powerful bite so you have to be careful when holding them. But they do go through several instars, taking days to weeks to years to develop, depending on the species. So things like the stag beetle, the larvae can take a long time to develop in the wood, the dead wood that it’s feeding from.

Then they pupate into fully-formed sexually mature adult beetles. So some examples of what some beetle larvae do look like, but if you are interested in learning more about beetle larvae, there is a guide that you can buy if you really are into them. Uh yeah, it’s not something I have gotten into myself, but it’s nice to know that there is something out there if I do ever find lots of different beetle larvae.

So beetle families, before I get into leaf beetles. The most recent checklist of British and Irish beetles is actually from 2012, so I’m basing it on this even though this is obviously completely out of date because in 10 years a lot can happen with species.

There are three sub orders of Coleoptera in the UK. You’ve got the myxophaga where there’s only one species in the UK, which is the bottom left image, and they’re very small and they live in seaweed, so I’m not going to say any more about them. The adephaga are the predatory ground beetles and the five water beetle families and everything else is lumped into the polyphaga and that includes the leaf beetles, the ladybirds and rove beetles. So this is literally most of the beetles that we have in the UK. But in the 2012 list it includes 4072 species, and 1246 genera and over 100 beetle families.

Now the leaf beetles are just one of them; the Chrysomelidae. Now they have themselves been separated into one superfamily, the Chrysomeloidea, and that includes the Chrysomelidae which is the vast majority of leaf beetles, there’s about 280 or so species, and then you have a further three species in Megalopodidae – I’m struggling to say that – these are very interesting, not ones that I’ve ever seen. They’re quite rarely found, to be honest. The larvae are leaf miners of trees such as aspen and poplars. So if you’re interested in leaf miners, it’s definitely one to look out for.

And then the other group is the Orsodacnidae and there’s only two species in that group, and I’m not really going to mention any more of them, I’m definitely not an expert in those two groups at all.

So we’re going to talk more about the family Chrysomelidae. Now there is huge diversity just within this family. They’re often seen as being broad, oval and brightly coloured. But not all are brightly coloured and I always find that really surprising with them.

So some do resemble ladybirds, but they never have clubbed antennae. So ladybirds, what characterises them are the clubbed antennae and then leaf beetles never have this. Some though have enlarged or expanded and tending towards the end, but it’s never a club.

So compared with ladybirds, the second antennal segment is at least half as long as the third segment, and the third tarsal segment is heart-shaped, and they’ve got 4 tarsi on each leg, so that’s where that image comes, whereas ladybirds’ tarsal segment number two is heart-shaped. And it’s quite important to remember those differences, because ladybirds are a group of beetles that you’re more likely to get confused with the leaf beetle than any other one.

And the UK, I was looking this up today, what our smallest leaf beetle species is, and there’s a couple of them that are about 1 millimetre long – absolutely tiny. But our largest is the bloody nosed beetle, Timarcha tenebricosa, and that’s fairly common down in the South of England, but in Scotland, where I am, I’ve only seen them along the Solway firth, which is one of our Species on the Edge project areas. But they’ve just obviously reached their limit and haven’t really gone elsewhere.

So this is the smallest one here is. I’m not sure I can say that, Mniophila muscorum, so obviously associated with mosses, but the other one is one of the flea beetles, Longitarsus minusculus. And it’s not easy to imagine that little beetle being 1 millimetre in length, but that is absolutely tiny for a beetle, whereas 18 millimetres is a big, big, chunky thing.

They’re also found, as I said earlier, worldwide, and we have some absolutely amazing global species that if you do want to have a Google search of tropical leaf beetles, you will come across all sorts of colours and varieties. The frog legged leaf beetle just looks spectacular. That’s found in Asia. The spiky leaf beetle from Borneo, there’s a few different species of them. Tortoise beetles are absolutely fascinating little leaf beetles, and you get some of them which are see through – its camouflage. The warty leaf beetle in the middle there at the bottom is a very small leaf beetle and it’s related to the pot beetles, which I’ll talk about later. And I was struggling to find another pretty photo of a different leaf beetle so I did stick in a Colorado potato beetle, which isn’t necessarily tropical, but it does look pretty cool, but it is a big pest species to our potato crops.

And that’s one I’m going to go onto next. So leaf beetles is a pest species, they do feed on plants. And I have to say I’ve never been a very good gardener because to me, plants are there to be eaten. So I see bugs on them I’m always quite excited. So leaf beetles, of course, feed on the plants; it’s not just the leaves. So some within the larval stage will feed on the roots, and they can cause significant damage to them, especially those that feed in large numbers like the celery leaf beetle, Phaedon tumidulus, you typically get that on hogweed and that’s an image that I took of that hogweed, that’s before they all did their drop and roll and then there was none left because they were all disturbed and they all dropped off down to the leaf litter. But dock leaf beetles can cause huge damage to docks, which I suppose we’re never really bothered about because we see dock as being a pest plant species, but there are some species of these beetles that can act as vectors of disease, such as the cabbage stem flea beetle, which can cause huge damage problems for farmers.

But there are others that by feeding on plants can control the plant pest species. I mean, you see the dock leaf beetle and the damage, how much the dock beetle can feed on the dock leaf. It is absolutely amazing and you can see why they can be used to help control those plant pest species.

Now, it’s not just leaf beetles that undergo cannibalism, but ladybirds do this as well. So some species are voracious cannibals after hatching, such as the willow beetle. And they do this in order to survive. So because they lay large number of eggs, often grouped together, when the first one or two hatch, they start feeding on their siblings and that makes them bigger and stronger, faster and more able to survive. But not all species do this, but ladybirds as well, ladybird larvae will, if they find another ladybird larvae, they they will eat it, especially if there’s not enough food present. I know this from past experiments at university, that didn’t necessarily go down so well, but anyway. But yes, it does help them with their survival rate, but they do have a whole range of mechanisms depending on the species, with where they lay their eggs to help the larval survive, especially because when they’re born, they are very, very small leaf beetles.

The adults as well can protect themselves through defence mechanisms known as reflex bleeding, so this is the bloody nose beetle which I mentioned earlier. And you were maybe wondering why it was called that if you didn’t know. It’s because if they are disturbed, annoyed or feel that they need to defend themselves, there’s this chemical defence, so drops of blood or glandular secretions are produced through slots in the membranes between the scelrites on the abdomen or within the mouthparts, this is a really nice photo that shows that quite clearly with the bloody nose beetle. It’s basically a deterrent that accumulates in the blood and doesn’t taste nice so if something’s trying to eat it, they will drop them, and that means the beetle then has a chance to survive.

So there’s many species within the Galerucinae family, both adults and larvae, that will do this to help them survive, but leaf beetles do have another defence, which is what I was talking about with the celery leaf beetle; when they’re in huge numbers – and in fact, not even when they’re in huge numbers – if you’re trying to take a photo of a leaf beetle, keep your eyes on it all the times because they will do this thing where they put tuck their legs into their body and they’ll just drop off the plant into the leaf litter below to try and get away and to survive which is obviously very clever, but it can be very annoying when you’re trying to take a nice photo of them and they all drop off one after another. So be aware of that if you do want to take photographs of leaf beetles. Careful how close you get, because they will sense you and then they will all drop off the plant.

And I suppose this is one of the reasons why I do love leaf beetles is that variation of colours and even within a species. So things like the Chrysolina variants, which is just what their name suggests, this species has got several colour varieties which you can see in that image I found online. So they’ll be bronzy, green, blue, purple – it really just does vary and some others as well. So the this is a pot beetle on the bottom left, Cryptocephalus bipunctatus, typically has red elytra, so the red wing cases with a black band. But this black band varies in size and can cover most of the abdomen or just a little bit, or the elytra or the whole beetle can be black, so it can be quite annoying when you’re trying to identify them if you have that variety, so it’s always quite a good idea if you find something to look for more of them, so there might well be examples of the species there within the different colour varieties that can help you identify the species if you are struggling with it being all black.

And again, that’s another thing that ladybirds do; when you look at the Harlequin ladybird, they’ve got over 100 colour varieties within the harlequins, but the 10 spot ladybird and the two spot, you have loads of different colour varieties and leaf beetles are very similar in that too.

Identifying leaf beetles; sometimes with all invertebrates, they can be quite tricky to get into because sometimes you need a microscope or a really strong magnifying lens, but not all of them are like that, because with leaf beetles you can look at the plant that they’re feeding on and that can help try and narrow it down. But if you are looking at the features on the beetle itself, that’s a really good idea to do and it helps you get to learn the names of the body parts. So like things like the scutellum where you can see in this image it’s pointing to that little triangle there, which is between the elytra and the pronotum and the suture, which is the line going off, the where the elytra meets, so it’s that line going down the middle. So they all have different names with the body parts.

But the key features for identifying; there’s a range of different body sculpturing, so things like depressions and punctures, whether they’re on the elytra, if they’re in rows or all over the place, if they’re really deep, or if they’re quite shallow as well.

But the shape of pronotum can be quite a useful thing to look at. If there are pits and pores, there might be sensory hairs that are pretty obvious. The legs and the antennae, so the colours and the shapes, but as I’ve already said, the habitat and the distribution of what plants they are found on can be useful.

You can use things like, I do have a list of useful resources that I have emailed to the organiser, Liz, who will aim to send that out. There is a web page on that that’s not necessarily going to help 100% at the time, but it’s just more for interest, but there is a website called insects and their host plants, so you can look up a plant and it will tell you all the insects that are known to feed on that plant which is really interesting.

So I’m just going to talk a little bit about some of the leaf beetles and some of the key things, some of the common ones to look out for, or the ones that might be fairly easy to identify, straightforward to identify, I should say really. These are just an example of – there’s a couple there that I will talk about – but things like the celery leaf beetle are one that I’ve already mentioned that is found on hogweed, so if you’re about in the summer, so say June to August and you see lots of what look like tiny black beetles – they’re only a few millimetres long – on a hogweed, it’s probably them. They’re often found in quite high numbers, and if there’s lots of damage to the hogweed it will probably be this species as well.

Then the dead nettle leaf beetle is a really beautiful, beautiful marked beetle that’s found on white dead nettle and red dead nettle. Another easy one to look at because of the plant that it feeds on, and it’s a really obvious one. So if you see any patches of dead nettles, especially white dead nettle, do look out for this beetle because it’s fairly obvious and it’s a nice one because it’s associated with a particular plant. But a little bit about the thistle tortoise beetle and the willow wood beetle in a little bit.

So I’m just going to go through some of the subfamilies of leaf beetles and some of the key things here. So the first one are the reed beetles, the Donaciinae and they include the species of Donacia, Plateumaris, and Macroplea. There’s not actually that many within the subfamilies, like 22 or so species altogether. And a lot of them are actually incredibly endangered and have Red databook statuses because not as much is known about them. They’re found in aquatic habitats, so like wetlands and reeds, round big ponds. There are some really common species. But as I say, lots of them are really rare.

Now I’ve put this diagram in which I’ve taken from one of the ID guides and if you do find a reed beetle, they’re a very distinctive shape. But the Donacia and Plateumaris, can be very similar in appearance when you look at them. And the key difference is that the Donacia, the elytra is quite flat, especially at the end of it. Whereas the Plateumaris, they’re more rounded at the end, so when you’re taking photos of things like beetles and want to try and identify them later on from your photo, try and get it from different angles because that can be really useful if we’re seeing features such as this.

And yeah, I’m not really going to say any more about reed beetles. I’ll talk a little bit about another subfamily, the Criocerinae. This family, this subfamily, I should say, it includes a few different groups, but the key feature here is their eyes are notched, so they’re not round. There’s a bit missing out of either one of them where the antennae fit in and that’s very similar to the longhorn beetles who have notched eyes because of the length of their antennae for them fitting on their face, to be honest.

One of the most obvious ones within this subfamily, which people will not like if you love your lilies, is the lily leaf beetle. Now, this is an interesting species because it was introduced to the UK from our garden centres, and it’s now spread across the country. I will say I did plant fritillaries in my garden in a previous house and was very excited to get a lily leaf beetle and did take, I think actually might be one of my images at the top there, because I did get quite excited with the camera just because they’re so pretty – my fritillaries were fine I have to say, they came back every year so they weren’t too bothered by this species, but I never had them in huge numbers and I know in some places you do get quite a lot. But the developing larvae feed by progressively eating entire leaves up the stem until only the flower remains and I have say they don’t look very pleasant. They’re basically keeping dropping their faeces on them to try and stop them being eaten. But the adults can be found all year and if you’re wanting to protect your lilies, people do pick them off, but yeah, it’s up to you. But I mean, I love these little lily leaf beetles, but I’m not a very good gardener. I’m more about attracting things like this to my garden.

But I’ve got an image here that shows what I was meaning with the eyes being notched, so you can see that at the top, the eyes aren’t completely round, they’re kind of a funny shape. And the other example there from this subfamily, just because it’s really pretty, is the asparagus beetle which is probably a pest to asparagus, so apologies for those, but it’s just such a pretty, attractive beetle that I had to include it as another example in this family because it’s just so lovely.

Now here’s the stuff I’m going to talk a little bit more about: this, the Chrysomelinae. They are the typical expected leaf beetle shape with the bright colours. They’re quite round in appearance. Within this group, the antennae are often thickened towards the tip, which you can see in the image of the knotgrass leaf beetle at the bottom.

But this group includes some of our charismatic species, like the bloody nosed beetle, but also the tansy beetle, which is quite a big leaf beetle. It’s a big chunky one in size. It’s like not quite a centimetre from memory. I have actually seen them. I was very lucky with Buglife to go to a site by York to see them in the flesh, so they’re absolutely beautiful; big chunky green leaf beetles. But if you see a green beetle out and you’re looking up books, and it’s not a tansy – this is a root tansy, it is very, very rare and it’s only found in a handful of places across the UK around by York and I think in East Anglia there’s records, recent records of them there as well. But we do get people calling in and emailing, telling us they found tansy beetle, but on a different plant, and it will be another species of leaf beetle because they are incredibly rare. But if you do live in York, it’s definitely worth going to have a look at them because they are very exciting beetles to have in our country.

But interesting within this subfamily is most feed on a limited range of plants, which is why I quite like this group. And yes, they are green and shiny, but it’s that relationship with the plants, like the tansy beetle, like the knotgrass leaf beetle which feeds on knotgrass, and it also includes the dock leaf beetle as well, but the bloody nosed beetle too, so the timarcha tenebricosa, they’re associated with bed straws. The larvae are chunky beasts as well, very distinctive. They lay their eggs in the spring and the adults are around during the summer. But they’re big and they are flightless and their elytra, so their wingcases, are actually fused, so they can’t open them. And if they end up on their backs, they have to use their legs to hook onto a plant to try and right themselves, so they can’t actually use their elytra to flip themselves over, which many other beetles do. So a lot of the big beetles we have, so things like the big ground beetles like the wiolet ground beetle, the Carabus species, are the same, their elytra are fused and they can’t open them so they need help to right themselves. They can’t do it themselves, silly beetles.

Well here’s the dock leaf beetle and what I really like about this species, if you find them, you can actually find basically all the life stages on one plant. So you can get the eggs, the larvae and the adults all on one plant, which is really cool. But they typically feed on dock but they have been observed feeding on other things like buttercups. But the females, with some of the leaf beetles you can identify it’s a female, this sounds really bad, but if they’re quite big, if their abdomens are quite large and fat, and that’s because they’re full with eggs. So they’re all swollen because they’re ready to lay their eggs. But this beetle here you can find it everywhere, I’ve seen it in various places across the country; where there’s dock, you will probably find this beetle. So it’s worth having a look out for it, especially the larval stages as well.

And now we have another species of Chrysolina. So the tansy beetle is a Chrysolina species, but this is the Rosemary leaf beetle, and I think the reason I included it in here is because it’s shiny and really colourful and another one that you’ll find in your garden that’s easy to identify and it’s also really interesting. So it first was recorded in the UK in Surrey in 1963 and has since spread everywhere due to garden centres and the fact that we moved plants across the country with no restrictions at all. So they do feed on a range of things, you’ll find them on you rosemaries and lavenders and sage, but they’ll also feed on dead nettle and other similar plants as well. The larvae again are big chunky things, very obvious if you’ve got them. And again, people don’t necessarily like them because of the damage they can do to the plants. But I if I had them, again, I would just like looking, watching them because they are very colourful.

Which gets me on to the plantain leaf beetle, and this is another species of Chrysolina. Now, this one’s very rare, completely different to the one I was just talking about, and many of the other ones I was just talking about. Chrysolina intermedia is basically black with these beautiful red stripes going along the edge of both sides of the elytra. And they are very restricted in range as you can see on our distribution map. In the UK, they’re only found in Orkney and Shetland. Now we’re working on Species on the Edge project, which we mentioned at the very start. Now just a tiny bit about the project. It’s a four year partnership programme with eight organisations funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund, NatureScot, Scottish Government and more. The main aims are to secure and improve the future of 37 threatened and often poorly understood coast and island species in Scotland and to empower communities to connect with one another and their local wild places and the special wildlife within and to inspire action and to build on synergies, collaboration and shared knowledge to maximise the benefits of a common agenda.

So Buglife are working with RSPB, Butterfly Conservation Scotland, Bat Conservation Trust, Plantlife, Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, Bumblebee Conservation Trust and NatureScot through this project, and it’s across, around the coast of Scotland, so it includes Orkney and Shetland, where the plantain leaf beetle is found.

Now the size of this species varies from 7 to 11 millimetres in length. I’ve already said it’s found in Orkney and Shetland, but there is a potential population at Glen Etive that I have been in discussion with other Buglife members of staff, so we’re wanting to investigate the population at Glen Etive because that’s a completely different habitat and it’s also quite far away from Orkney and Shetland too. So we want to investigate that population and see if it is that species and how closely related they are, if we can do some DNA analysis as well. So it’s quite exciting.

But this species here feeds on plantain, so plants in the plantain family, so things like sea planting and buck’s horn plantain, which you get both of them on Orkney and in Shetland. You get them also in other places as well across the country, so who knows why it’s not found further afield. But that’s what is quite interesting about many of our leaf beetles. So things like the tansy beetle, you get tansy across the country, but for some reason you do not get the tansy beetle across the country. And I think that’s why I’m quite interested in, and especially this plantain leaf beetle, because plantain is literally everywhere, so there’s something going on with these beetles that restricts their range.

So they reproduce. They over-winter as adults, hiding within the base of plants, and they come out to feed on warm, sunny days. Adult females lay eggs from about March. So there has already been records of these beetles being active at the end of February, showing signs of laying eggs on buck’s-horn plantain, according a Facebook group, to do with insects in Orkney which is really exciting to hear, that they’re already out and about. And let’s hope that that continues.

So, we’ve included them in the Species on the Edge project because they are so restricted in range, but they are within the projects that were being developed in Orkney and on Shetland and even the staff working on the North Coast are really interested in the species because it is similar habitat along the North Coast of Scotland in places to Orkney.

So we’ve included it within the project and the aim is to do more because the population trend of the species, it is declining, it’s classed as Nationally Rare within the UK and Endangered on the IUCN Red List, which is an international list of species that are threatened with extinction or are vulnerable to extinction.

So the main threats to this species are loss of habitat through erosion from the collapse of cliffs, overgrazing and recreation by people because they are usually found in cliff-top grasslands. I’ve got a photo there at the bottom of one of them in its habitat. So it’s really interesting habitat that it’s found in. Through Species on the Edge, we want to learn more about this beetle, its distribution and its requirements, and if there is a population at Glen Etive, even better, we will try and find that out too.

So we have put together a protocol to help staff in Species on the Edge and volunteers in Orkney and Shetland and potentially the North Coast to do some transects and monitor sites, and I’ll be going to Orkney in a couple week’s time to do some training for the Species on the Edge staff and volunteers, so for the rest of Species on the Edge project, which is another two years, we’ll try and learn a little bit more about this really beautiful beetle.

Now on to a different subfamily, because I absolutely love the tortoise beetles. Very different to the leaf beetles I was talking about, because they often sit flush with the leaf so they can be really hard to see and you can’t see the head from above, so this example here is the thistle tortoise beetle, Cassida rubiginosa, and they actually are really hard to see, I think that’s a photograph I took of a doc, they’re very well camouflaged. That individual there, I remember watching this strange creature fly – if you ever see an insect that looks weird when flying, it’s probably a beetle because of their elytra, the way they have to stick them up. But they do fly and absolutely amazing to watch.

The larvae of tortoise beetles are really interesting, so they’ve got these twin tails that are used to carry the discarded skin. So as they moult, they keep a hold of their moulted skin and they use it as a parasol and that helps disguise them from predators. But this particular species here, you can find the larvae on creeping thistle quite easily if they are in the area and it’s a widespread species across Scotland and the whole of the UK.

One of the largest families, sub families, Galerucinae and they include two tribes. So they include the flea beetles, which is most of them, and everything else that isn’t a flea beetle. Everything else that isn’t a flea beetle includes things like heather beetle, Lochmea suturalis, which is associated with heather and heaths, and you can find the adults again all year round. If you are in a location with heather and you see beetles that look like this, it will be this Heather beetle and there can be hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of them. You can get them in huge numbers. But they’re found in almost any habitat where there is heather and they are very similar in appearance to the willow leaf beetle; If you’ve not seen either of them for a while, even when I see them, I go, “oh, that looks like a Lochmaea but it’s on willow, so it’ll be the willow leaf beetle”. There are differences, though, so they’re distinguished by the yellowish brownish mark on the black head and suture along the elytra, narrowly darkened compared with the heather beetle which is slightly different, but again, using the plants can be really, really helpful, especially when you’ve got lots of willow and then lots of beetles that look like this all over the willow or as I say on the heather.

Most of our species of leaf beetle in the UK are a flea beetle and they can be quite challenging to catch, I suppose, but also to identify because they’re quite small. But if you are really interested and you have a microscope, you can look for the key features and so again a lot of them are associated with plants, but some of them can feed on a huge range and there’s lots of them that can feed on the same types of plants. So you do need to be careful.

The Longitarsus is one I mentioned earlier because it’s one of our smallest ones, but this is a different species associated with ragwort. Now on their hind leg, one of the segments is just really, really long, which is what Longitarsus comes from. So it’s a easy character. And generally if I get stuck, if I even if I get to a genus I go well, at least I’ve gotten somewhere with this beetle, and that’s still a good record to have if I’m not able to take it further.

But they all have hind legs that are enlarged and modified for jumping. And yes, they can jump quite far. And it’s always really cool if you have an insect that can jump, you can feel the pressure of it as it jumps off your hands.

The key ID features for the species, as well as looking at the plants that they’re on, but it’s the groove on the pronotum and the features of the hind leg. But yeah, please be aware that you might need to examine it under microscope, and sometimes it’s just knowing that I’m looking at a flea beetle. I’m happy with that. There’s 127 species. I’m fine. Just depends on how into it you want to get into.

And one of the last, I think this might be the last subfamily that we’re going to talk about are the pot beetles and like the Reed beetles that I spoke about at the beginning, many of these, the vast majority, are rare. So there’s 24 species within the subfamily, and not all of them are Cryptocephalus but I think when I looked at this before, 14 of our 19 species of Cryptocephalus have conservation designations. They’re just incredibly rare.

But then you also have species like the Clytra quadripunctata which is the bottom image there. This is actually associated with the nests of wood ants and I have been really really lucky to see adults of this species twice, once in Scotland and once in France. They are big, beautiful, beautiful beetles.

So the key features of pot beetles is, and what their name comes from – Cryptocephalus – is their head is kind of hidden underneath the pronotum. So they are quite parallel sided, but it’s on the underside, the 4th abdominal sternite is strongly constricted in the middle, which is very obvious if you’ve got a hand lense and you see a beetle that looks like you can’t quite see its head from above. If you look on Birch, there is – I can’t remember the full species – but there is a Cryptocephalus type of pot beetle that you find quite regularly on birch. A little black one.

So they’re called pot beetles because of the larval stage; the female lays her egg and holds it underneath her and covers it in her own faeces and then drops the eggs. When the egg hatches the little larvae lives in a little pot of poo, hence the name pot beetle. And as the larvae gets bigger, it just adds to the pot with its own waste and crawls about until it’s ready to find a place to pupate in leaflitter before emerging as an adult. And here we have a little picture of a pot beetle larvae in its little pot of poo.

But this is one of my favourite beetle species, beetle species in general, the six spotted pot beetle. I’ve been really lucky to see this beetle and it’s very rare in the UK, only found in a handful of sites; in Scotland it’s found around Kirkconnell Flow in Dumfries, that’s the only place that I’ve seen it in Scotland. But it’s very attractive. Adults emerge from around mid-May and they’re actually not active for very long, kind of a couple of months at the most.

And interesting that they’re quite rare because this species in particular is associated with quite a few different plants as you can see from that list. So some willows, birches, hazel, oaks, hawthorne, aspen and broom. Those are all the plants that I’s been observed feeding from. So there’s something going on, but they like young leaves and this is where I think a lot of leaf beetles will be the same, and a lot of other animals are the same, they like the taste of young leaves because they don’t have as much tannins and other chemicals that have been built up by the plant, very much tastier for them.

So just a bit of a recap with other beetles that could be confused with leaf beetles, I mentioned this earlier, the ladybirds, there are 46 species in the UK, characteristic bright colours, just like leaf beetles with spots. And so remember this is the six spotted pot beetle, it does have spots. But ladybirds have short and clubbed antennae; leaf beetles, remember, never have clubbed antennae. And the tarsal segment on the legs are different. So in leaf beetles, the third tarsal segment is heart-shaped, whereas with ladybirds, it’s the second tarsal segment. And you can see that in that awful image that I’ve managed to combine there.

Now, where do we find ladybirds? Leaf beetles and ladybirds actually. Basically anywhere. If you’re wanting to, if you’re interested in looking at reed beetles, definitely look around your wetlands, your ponds on the reeds themselves, brownfield sites such as on the top right, they can be really good because of the poor nutrients in brownfield habitat, because of the disturbance by man it’s perfect for allowing a diversity of wildflowers to develop that don’t like nutrients. So because you get high species diversity of wildflowers and other plants you often do find lots of different types of leaf beetles their feeding on the different plants.

Woodland edges can be quite good for leaf beetles, so things even like docks, the dock leaf beetle, and Rosebay Willowherb as well can be quite good for a whole range of them. There’s a really interesting leaf beetle, Bromius obscurus, which in America it’s classified as a pest species, but over here in the UK it’s quite rare. It seems to be spreading or it seems to have been in the last two or three years, recorded from several new sites. But in Scotland it’s only found in Jupiter Wildlife Centre in Grangemouth and it’s associated with willowherb, which you know is a plant that you get absolutely everywhere which is really interesting.

But our gardens as well can be good places, if we’ve got really biodiverse gardens, you never know what you’re going to find. It depends if you want to find them in your garden, if you’re quite happy going to maybe a community garden where you might get them. But it’s looking at different places and looking under leaves as well for the larvae. So if I find a leaf that looks like it’s been nibbled, I have a look, it might well be a snail or a slug that’s been nibbling it, but I always have a look because it could well be a caterpillar or a leaf beetle.

And different techniques, you can just look which is what I do, hand searching on plants and under leaves. You can look on the flowers or you can use things like a beating tray. You don’t necessarily need to buy a fancy beating tray. You could just use an old cloth or an old sheet on the ground or sweeping vegetation, if you’ve got a little net you can use that to sweep the vegetation. Keep in mind that you don’t want to sweep for too long, because if you sweep a leaf beetle and you don’t know what plant you’ve swept it from and you don’t know how far you’ve gone with your net, it can not help with the process of trying to work out what that leaf beetle is. So I generally use my hands or eyes for looking if I’m wanting to look for leaf beetles. Sometimes though, I will use a sweep net if I’m looking for other things at the same time.

Now the reasons for recording leaf beetles is not just because they’re green and shiny, which is what I’m interested in – the colours – it’s because it’s important to record anything and everything, even things like the seven spot ladybird. Because if we don’t know it’s there, how do we know what’s there and how can we protect a site if it comes up for development, or if we’re at risk of losing it or for whatever reason. It helps us generate reliable records that can then be verified, so using things like iRecord is a really good way for recording anything, and you can upload photos for verification and that all feeds into national recording schemes.

You can develop your own reference collection if you’re interested in that with either photos, which is what I do, or with actual specimens. So some people do like to collect specimens and have as a collection, and as I said earlier, if you’re doing a survey of a site and you have leaf beetles and some of them will, like many invertebrates, you do need to use a microscope to identify them, so that’s where collecting specimens can help you identify them and get that record confirmed.

But promoting the study of beetles in general, beetles are absolutely fascinating. There are things out there that can help you. There’s a leaf beetle recording scheme, which is part of the UK Beetle Recording scheme, and it’s got information on the family where you can go to for help. So Dave Hubbell used to be the coordinator of the Leaf Beetle Recording Scheme, but he has obviously stepped down and it’s someone else and have forgotten their name. But he’s produced the keys to the adults of Seed and Leaf beetles which is a book that I regularly use. I’m probably one of the few people in Buglife that actually has a copy of the Atlas, I’m probably the only person in Buglife that has the Atlas of the Seed and Leaf beetles of Britain and Ireland. It is completely out of date because it’s from 2007, but the information within that about what plants they feed on and about what parasitoids might affect them and when they emerge and are active, is still very relevant. So it’s one of the books that I use the most for some bizarre reason.

But if you’re just interested in some background information to leaf beetles, the Naturalist Handbook is quite good. I can, I will say it could be a bit better with the images that they use, but the background information within that is very, very good.

And here’s the link to insects and the host plant and that can be used for anything, to be honest, you can get carried away with that and you just end up looking at all these random bugs and you forget what you’ve gone on there for you. You went on to look for one particular plant to find one bug and you’re looking at all sorts of other stuff so it’s a fascinating web page to look at.

I’ve already mentioned iRecord for recording. What’s good about our iRecord if you haven’t used it is you do get experts that verify your record and that’s why having a photograph can be really good. If you do get stuck with identifying things, there are some groups on Facebook that I would like to say are really, really good for helping. They’ve helped me when I’ve had queries in the past, so it’s invertebrates of Britain and Europe, I think it’s called, and you can upload some photos and ask people to help you, but remember to give your location and if there’s anything else about size, especially with the leaf beetles and what plant it was on as well.

But you know recording, it allows everybody and anybody to get involved in science and conservation. But there are other websites as well. So there’s Wild about Britain, iSpot, iNaturalist, all sorts of different web pages out there that can help you with your IDs hopefully and recording.

And that is me done. Thank you very much.

00:59:05 Sally Morris

Thank you very much, Susie. That was amazing. I always find it just such a delightful presentation to look at. All the colours. They’re just delightful, aren’t they? But I also learned a massive amount from that. So thank you.

00:59:23 Suzanne Burgess

I hope I haven’t overwhelmed everybody now.

00:59:26 Sally Morris

There’s quite a lot of information. Beetles are quite an overwhelming group. Yeah. If anyone has any questions, please feel free to put them in the chat. I’ve also just put a link to our evaluation form. If you can fill it in, that would be absolutely amazing. Any feedback you have will help us with our next series of talks next winter.

So Susie, there’s already a message from Sarah in the chat saying do adult leaf beetles always eat the same thing as their larvae? And what about other types of beetle?

00:59:59 Suzanne Burgess

No, they don’t. So some of the larvae will feed on things like the roots of the plants, and then the adults will feed on the actual leaves of the plants. It just depends on the species and I’m trying to think of an example, but I can’t at the moment, but honestly the naturalist handbook is very good. It does have information about the different stages of the larvae and what they all feed on as well. That’s what I’m trying to say.

Now I’m just going to flip through the book. Oh my goodness me, I’m terrible. And other types of beetles too. So yeah, larvae and adults, there are those that feed on different things. So things like stag beetles, the larvae feed on decaying wood and same with things like the longhorn beetles, the larvae will feed, or the vast majority of Longhorn beetles feed on decaying wood, they’re saproxylic species, whereas the adults are actually pollinators, pure pollinators. beetles are pollinators, but they’re not as good as bees. I always have to remind people that, they do pollinate, but they’re not very good at it because they’re not as fluffy as a bee. But that’s what’s really interesting about beetles and it’s about all invertebrates, we can’t just focus on what the adults require within the habitat, it’s what their other life stages require as well, which is really, really important to remember so that we don’t just go oh, we need lots of dead wood for longhorn beetles when actually the adults feed on pollen. So we also need areas that are open for flowers to grow.

01:01:56 Sally Morris

Thank you. There’s another question from Rob’s saying: for iRecord, how often should you submit a record if you see the same type of beetle every day, should you submit a new record every day, once a month, once a year?

01:02:12 Suzanne Burgess

I suppose if you were doing a survey that you were surveying the same area every day, if you wanted to do that, you could record it every day. I think that through iRecord that you would just be creating the same record of potentially the same individual, but it might not be the same individual, you’re not really going to know that. I don’t put things on iRecord all the time because I’ve got really bad memory but what I try to do is do it in little chunks. So I will have a day where I’ve got a list of records with the photographs and I will stick them on. But I don’t generally record the same thing over and over again just because it can… It is a good question. I’m not really sure how to answer it actually, but if it was exactly the same individual you probably don’t want to record it. You could maybe put something on it so you then know it’s the same individual, but if you saw a different one then you can record that one so then they know that there’s more than one in the area.

01:03:24 Sally Morris

Yes, I think that’s quite a tricky question depending on, I mean, even when I survey for beetles, I’m obviously only going out there for a week at a time, but lots of other people might do monthly transacts or maybe they’re looking for the first emergence of that beetle, because that’s quite interesting information, if that changes year on year. But yeah, a tricky one I think depending on how much you can be bothered really. But all data is good data.

01:03:53 Suzanne Burgess

Exactly it is and you can just record the genus as well. So if you’re unsure of the species, so say you knew it was a species of one of the flea beetles, so you know the genus, but you don’t know the species, you can definitely just put genus in. You could also do family as well. Knowing that a family’s present can be in itself really important, so especially if it’s like a rare group of beetles or other invertebrate, but sometimes it can be a bit like, well, it could be anything, especially if you’ve got like 1000 different species within that family. Well, it doesn’t really matter if that means something to you, though then definitely go and do that.

01:04:48 Sally Morris

The couple of other questions about submitting to your county recorder or using iNaturalist as well, is that a good app to use as well as iRecord.

01:04:59 Suzanne Burgess

I use iNaturalist if I’m struggling to identify a plant, so if I’m at like a nice walled garden and there’s some nice plants that the bees are all on, I use iNaturalist to help me identify that, maybe not necessarily identify, but provide me with options that I can then look at and go., ah OK, it’s potentially this one. I’ve not actually uploaded any records on to our iNaturalist because I generally just use iRecord and it’s finding the app that works for you I suppose. So iNaturalist can be quite helpful in providing suggestions of what you might have seen, whereas I don’t think iRecord really does that.

01:05:46 Sally Morris

Yeah, I think it is a bit of a personal preference, isn’t it? The county recorders can be incredibly useful. It really depends on their capacity and how many records are being sent from any one person. But they can be brilliant. So if you do have contact details for county recorders feel free to contact them.

This is quite a tricky question from Lucy. Is there one particular recording site that is used more than others by planning surveyors, for example in assessing sites?

01:06:18 Suzanne Burgess

Well, they probably would go to their local record centre and the local record centre would have access to, well, the data that they’ve got so they’ll have access to things that have been submitted to the National Biodiversity Network Atlas. So the NBN. But they should have access to other data as well, at a cost to the planning surveyors. So local record centres are really good as well. I’m up in Aberdeenshire so I use NESBReC, I can send them my records directly or what they’re happy for is they download them off iRecord.

So once they’ve been verified, they can do it that way. So whatever’s easiest for you, because then they’ve got them verified, which helps them.

01:07:23 Sally Morris

Louise has put a lovely link in the chat for how to use iRecord if you’re not used to it.

And Sarah, who also works for Species on the Edge, has said that she thinks sending records to local record centres or county recorders is the best option. There is a backlog on I record sometimes so it can take a couple of years sometimes to get your records verified which is a bit of a shame.

01:07:52 Suzanne Burgess

Yes, because it’s relying on volunteers, isn’t it? And some of the groups, there’s not really anybody there to verify them. I’ve also had it on iRecord, when I’ve recorded things like roe deer or grey seal that they won’t accept records if they don’t know you, and I’m like well that’s fair enough, but I’m not sure how difficult it is to get that record wrong. But anyway, some people obviously will be getting that wrong, but, yeah, that totally puts people off, so I’m like, well, I’m not gonna bother recording then because you’re not gonna accept my records.

And how do you find out about your county recorder? So, if you look up whatever county you’re in and local wildlife record centre, hopefully it should come up with something. Would have thought so.

01:08:58 Sally Morris

Yeah, I think so. I think it depends on the record centre, but usually there’s something on their website with an e-mail from their local recorders.

Otherwise contact, I don’t know…

01:09:13 Suzanne Burgess

Yeah, local Wildlife Trust Mike’s put in, yeah, that’s a that’s a good shout, they should know who the county recorder is as well.

01:09:23 Sally Morris

Right. Are there any more questions, anyone? If anyone suddenly has a question once this meeting’s over, feel free to contact any of us really. You can contact the Scotland Buglife e-mail which is Scotland@buglife.org.uk and that can be forwarded on to Susie or you can contact Species on the Edge and I’m sure we can get back in touch and answer your questions.

This is all being recorded, so if anyone would like to look back on the recording, it will be available I think in a in a few weeks just because of capacity, trying to sort out the editing and everything, but it will be sent around with various links that Susie’s put together that will be useful for ID and things and the websites she’s mentioned today, along with our evaluation form as well. If you don’t get a chance to fill it in today.

Thank you very much for coming everyone. It’s been really brilliant. Thank you, Susie. It’s really, really lovely. Lovely to hear about beetles. All right, I hope everyone has an excellent evening and thank you for coming.

Further Resources

- The Coleopterist Society has a page dedicated to the Leaf beetle national recording schemes

- National Biodiversity Network Gateway for distribution maps of different species: https://nbnatlas.org/

- UK Beetle Recording – Beetle families: https://coleoptera.org.uk/beetle-families

- Mike’s insect keys – key to a range of other beetle families, including leaf beetles: https://sites.google.com/view/mikes-insect-keys/mikes-insect-keys/keys-for-the-identification-of-british-beetles-coleoptera/keys-for-the-identification-of-british-chrysomelidae

- Harde K, W (1999) A field Guide in colour to Beetles. Blitz Editions.

- D. M. Unwin (1988) A key to the families of British Beetles. AIDGAP

- Coleopterists Handbook 4th edition. Edited by J. Cooter & M.V.L. Barclay

- General insect guide: A comprehensive guide to insects of Britain and Ireland by Paul D. Brock (Pisces Publication) a good guide to all insects: https://www.nhbs.com/search?q=A%20comprehensive%20guide%20to%20insects%20of%20Britain%20and%20Ireland&hPP=60&idx=titles&p=0&fR%5Bdoc_s%5D%5B0%5D=false&fR%5Bhide%5D%5B0%5D=false&fR%5Blive%5D%5B0%5D=true&qtview=197401

- The Biological record centre webpage on insects and their host plants: www.brc.ac.uk/DBIF/homepage.aspx

- Atlas of the seed and leaf beetles of Britain and Ireland by Michael L. Cox (2007). Out of print but may be able to pick it up from another website: https://www.nhbs.com/atlas-of-the-seed-and-leaf-beetles-of-britain-and-ireland-book

- Key to the adults of seed and leaf beetles by Dave Hubble – Identification book available from FSC, requires a microscope: https://www.field-studies-council.org/shop/publications/seed-and-leaf-beetles-aidgap/

- Naturalist Handbook on Leaf beetles by Dave Hubble – number 34 from Pelagic Publishing: https://www.nhbs.com/2/series/naturalists-handbooks

- A review of the scarce and threatened beetles of Great Britain: The leaf beetles and their allies (NECR161): https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6548461654638592

- A guide to Coleoptera larvae by Peter M Hammond, Jane E Marshall, Michael L Cox, Leslie Jessop, Beulah H Garner, Maxwell VL Barclay (RES Handbook): https://www.nhbs.com/search?q=beetle+larvae&qtview=223710

- British Entomological Natural History Society. The Society run identification workshops and these may also cover leaf beetles: http://www.benhs.org.uk/events/

- Royal Entomological Society invertebrate keys (out of print and free to download): https://www.royensoc.co.uk/out-print-handbooks

- For help with identification can add pictures to Facebook group, Insects and other invertebrates of Great Britain and Europe: https://www.facebook.com/groups/invertid/

- iSpot: https://www.ispotnature.org/

Entomological supplies

- Watkins and Doncaster: http://www.watdon.co.uk/

- NHBS: https://www.nhbs.com/